I met Victor LaValle at a literary fest a few years ago. While handing him a copy of The Changeling, which was his latest novel at the time and the book I had just finished reading, I said to him, “I feel like I’m the person you’re writing these books for. You’re writing these books for me.” And I meant it then and I mean it now. There’s a point at which LaValle started writing the books he knew he was meant to write (he has said as much in his speaking engagements and lectures and in Q&As). Books about Black people. Books about Latine people. Books about immigrants. Books that take place in big cities where different languages are spoken in the same room, on the same streets, cutting between one another, rising above one another… all a dance of people who are all different, who are all the same. It feels modern and it feels real. It’s an authentic setting and tone from a person who knows what it’s like to be one of those people mixing at the mixer, dodging into the alleys, jogging for a train they’ll miss, shouting a sandwich order at the counter above a cloud of conversations everyone else is having.

Lone Women is so different and no different. I’m not tagging this book thoroughly because I don’t want to spoil it and the reality is that I want to spoil it. The book pays off in the story and with the story, but it also pays out beyond it. My recommendation to anyone who reads it is to do yourself a favor and read the Acknowledgements. Dear Reader, I cried. I felt that swell of pride that cannot be contained. The pride that unleashes tears. The solidarity with the titular “lone women,” only one of whom you would call your MC. By the end, the lone women have become a collective. The book goes from the story of one woman – Adelaide – and her burden to the story of all the lone women of the West and, perhaps, all the lone women of all time. LaValle provides context for the novel and lists his inspirations. Books he recommends as a suggested reading list if the story piqued your interest.

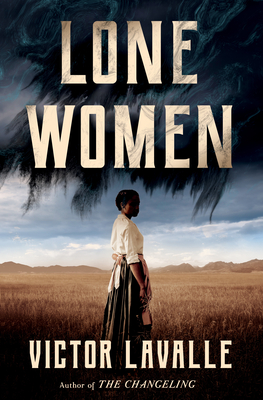

Now to the story: Lone Women is a historical fiction, a horror novel, and a speculative fiction work. It follows a thirty-one year-old Black woman named Adelaide who we meet as she tucks the bodies of her slaughtered parents in bed and lights the house on fire. She leaves town with a steamer trunk that’s padlocked and weighs approximately a gajillion pounds. She’s running away less than she is running to something. She’s read about homesteading women in Montana and how the US government is giving land to folx – Black or white, female or male – who can work it for three years. It’s a hard life, but it’s a life that can pay off with what then was just the start of what we call “the American dream.” To LaValle, that’s a myth. That’s a big ol’ con dressed in the fantasy of empowerment and independence. In the novel, there’s no lecturing. No finger wagging. No American history lesson in long blocks of text. To Adelaide, it’s a possibility in a way. It’s an opportunity, sure, but it’s also the only way out. Out of Glendale, the Black farming community where she was born and raised. Out of the margins of that community, of her whole life. Montana is, for Adelaide, the possibility to live something of the live she never had. To be free. What she drags along with her, though, is the burden her family bore and the burden she must now bear… or does she? Does she have to bear it? And what is it, anyway? Some things just don’t really exist, do they?

I don’t actually want to write any more about the story because it’s more than Adelaide and her trunk. It’s a Western in that it takes place in the West. It’s a horror in that there’s a lot of blood and gore. It’s speculative fiction in that it takes very real human situations, the very real American history, very real historical and current social “issues,” and people and situations we can recognize in our contemporary world and interrogates them in a fantastical or magical realistic way to help expose us to possibilities of what the world can be or how we can survive in the world as it is. The draw back, to me, is that it moves a bit slow through the first half… maybe through the first section. (The novel is broken up into three parts though I would argue it’s unnecessary to have “parts” at all.)

The last third of the book moves at a clip. Total high note last third.

And then, of course, that Acknowledgements section. Hey, LaValle. That was a damn fine book. Always ready for the next.