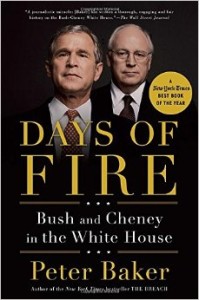

It is only fitting that perhaps the most contentious presidency of my lifetime gets a second look in my quest to read a biography for every president in US history. And while Decision Points was shockingly insightful and somewhat changed my opinion of George W. Bush, Days of Fire is far deeper and considerably more thorough. In many ways, this is for Bush what Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals was for Lincoln: an interwoven narrative exploring the characters of the particular administration being studied. And Baker, as a White House correspondent for the New York Times, did his research.

It is only fitting that perhaps the most contentious presidency of my lifetime gets a second look in my quest to read a biography for every president in US history. And while Decision Points was shockingly insightful and somewhat changed my opinion of George W. Bush, Days of Fire is far deeper and considerably more thorough. In many ways, this is for Bush what Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals was for Lincoln: an interwoven narrative exploring the characters of the particular administration being studied. And Baker, as a White House correspondent for the New York Times, did his research.

This book serves as both a welcome companion to Decision Points, for its full exploration of the administration and its faults, and a counterpoint to Bush’s almost pathological need to prove that he was the one responsible for his administration. This need, while understandable given detractors’ assumptions that Dick Cheney was the one making the decisions, is somewhat perplexing considering his willingness to grant so much power to subordinates. He fed the criticism for much of his first term in office, and compounded the problem by letting loyalty override his need to change course. The fundamental point Bush glosses over in his memoir and this book so brilliant encapsulates is that the Bush White House was not kept in order.

Early in his administration, Bush may have been in charge, but he allowed a great deal of his power to at least be funneled through Dick Cheney (if not siphoned directly off), and that much of the in-fighting (namely between Rumsfeld-Rice and Cheney-Powell) made day-t0-day operational efficiency disappear and long-term planning virtually impossible. Bush seems to write this off as loyalty on his part, but the impression I get from this account (which relies on broad research into all the parties involved) is that he was often above the fray, removed from the pissing contests and chest thumping. It wasn’t so much that Bush was a front for other powers (as the criticism often depicted him), but neither was it that he served as the nexus for a group of disparate but capable players. I think it more likely that Bush selected his cabinet because he liked what each of them brought to prior administrations (from Richard Nixon to his father, George H.W. Bush), and assumed they could work together under him. They often couldn’t, and were even very different people from who they once had been (Dick Cheney).

The key failure of the Bush administration was, in fact, the administration itself. The squandering of good will after 9/11 was a failure of diplomacy due to Bush’s inexperience, Cheney’s obsession with national security, the circumvention of Powell, and the inadequacy of Rumsfeld. The failure to find WMDs, and the Iraq War itself, was a concerted effort on the part of key players within the administration (among them: Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz) to find an excuse for war, and Bush’s failure to adequately vet the intelligence. Katrina was a failure of leadership unmitigated by strong and capable support from the people who’s job it is to support the president.

It’s hard to read this book and not come away with the feeling that the people Bush surrounded himself with were incapable of doing their jobs. Who, then, do you blame? It’s not a question I can answer, nor does Baker attempt to do so, here. But he goes a long way towards setting up the key players and provide the context in which their actions make some form of sense (if only to themselves). He does a marvelous job humanizing Bush and his cabinet, and showing not only what they did, but why they chose to act the way they did.

Days of Fire is as comprehensive a study of the Bush administration as you’re likely to find, and it’s a must read for anyone with an interest in the subject.