Content note for book and review: Grooming, addiction, domestic violence

Content note for book and review: Grooming, addiction, domestic violence

So I’ve recently got into writer/comedian/actress Chelsea Devantez‘s podcast Glamorous Trash, which does deep dives into celebrity memoir and generally unpacking celebrity myth making and narratives in a funny, thoughtful, sometimes poignant, and very incisive and sympathetic way. I listened to the episodes about the memoirs I’d read, and then ordered a bunch more that looked interesting to read before listening to their episodes. (Do other people approach podcasts like book series/binge-watching, whereby they listen to all the episodes before moving on to the next podcast? I feel like I’m Doing It Wrong.)

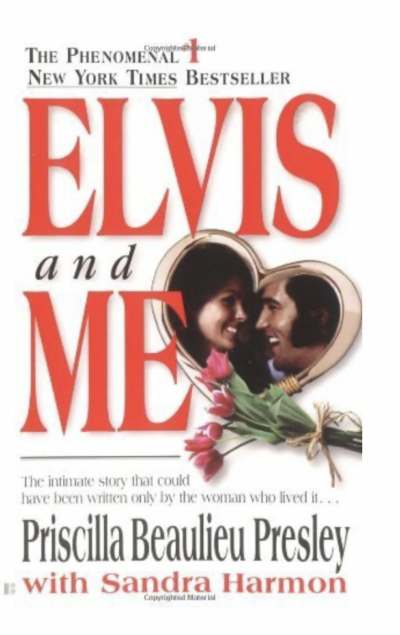

Anyway, I watched the Sofia Coppola film Priscilla (2023) a while back, so I thought I’d start with Elvis and Me–and oof. This story is troubling as hell–which the film shows clearly, but the book does not seem to fully realise, or perhaps is reluctant to explicitly state. There are, after all, still a lot of Elvis fans around, and 1985 was still, as Devantez points out, close to the actual events.

Priscilla is scouted to be a companion for Elvis when she is 14 and he is 24; they’re in Germany on a military base in the aftermath of World War II. Elvis is worried that he’s losing touch with his fan base back in America; Priscilla sort of becomes the stand-in for millions of screaming teenaged girls, I think, though she views their burgeoning relationship through the lens of teenybopper romance because she is fourteen. They have a tortuous relationship during which she becomes addicted to the thrill of being desired by him–and desires him in return because he is Elvis and she is fourteen and he is all the boy and man she has ever known, really. Eventually they persuade her parents to let her go to Graceland with him and finish high school there; she is made over in his image–he gets her to dye her hair black so it’s more like his–and eventually they get married and finally consummate their relationship which has become this weird game of sexual tension, manic spending sprees and wild shit like bulldozing a cabin and randomly buying a ranch, increasing use of sleeping pills and uppers, and being hounded by the press.

There are also moments of temper and violence, which Presley describes in oddly flat, matter-of-fact terms–she is very embedded in Elvis’s orbit and we get far more insight into his mood swings than her fears or regrets or anxieties. In fact, and I might well be wrong, but the impression I got is that her raging lust for Elvis (which he continually thwarts until their marriage) and her raging jealousy of the starlets to whom Elvis is linked are the only emotions she actually allows herself to feel during these years–everything else is constantly suppressed, whether by pills or new dresses or active choice

We had a few quiet moments together in his room. He asked how I was doing, if I liked school, and if his daddy was taking care of me. I started to tell him everything I hadn’t been able to on the phone, that I had missed him, that I had been lonely, that I really wanted to find a job. Then I stopped myself. This wasn’t what Elvis wanted to hear. (127)

It’s a fast read and an uncomfortable read; it’s an interesting portrait of an era not that long ago, shaped by power dynamics and gender roles that still linger, and it’s an interesting insight into a pop culture moment. It’s fascinating in what it reveals and doesn’t reveal; Elvis remains a “special man” to the bitter end, when Presley is an adult woman who has found the strength to divorce him and find her own life, albeit within the shadow of the Graceland estate and further tragedy.

Title quote from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955).