CBR15 BINGO: North America, because Thomas Dent Mütter was an American physician, and his museum is located in Philadelphia, PA.

CBR15 BINGO: North America, because Thomas Dent Mütter was an American physician, and his museum is located in Philadelphia, PA.

When I heard there was a book about Thomas Mütter, I knew I had to read it. Some years ago I visited the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, which is a museum of medical history that “displays its beautifully preserved collections of anatomical specimens, models, and medical instruments in a nineteenth-century ‘cabinet museum’ setting.” A quick walk through the museum’s site should give you an idea what you’re in for: some of the items on display include medical instruments from the 17th and 18th century; human skeletons warped by various diseases and hardships; kidneys; bladders; gallstones. The site’s FAQs note that the collection comprises “human remains, some displaying genitalia, traumatic injuries, or disfiguring pathologies which may be disturbing to young children.” But just because you can’t bring your young child to see the specimens doesn’t mean you can bring home a surprise from their gift shop, which boasts plush hearts, brains, and even microbes.

Be the hit of your next Secret Santa with this chlamydia microbe plushie!

I’m being flippant, but I want to assure you that the museum is a serious place that is respectful to those who donated their organs or bodies to the collection. Still, it isn’t a good choice for people with weak stomachs.

When I visited the museum, I didn’t really get a good sense of what kind of person Thomas Mütter was, so I wasn’t sure what to expect from this book. While I didn’t necessarily think he exploited people for his “curiosities,” I probably expected a dark personality, somebody who reveled in the macabre. What I learned from Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz was much more satisfying: Mütter was a kind man and an excellent teacher who genuinely wanted to help people.

Orphaned at a young age, Thomas Mutter (who added the umlaut to his name later because he liked the looks of it, and I love him for that), had a guardian who funded his education–to a point. He didn’t have unlimited funds was expected to earn a living. He decided to pursue surgery as a career (because, why not?), and when he went to Paris to study, he discovered les opérations plastique. This was in 1831, before anesthesia was invented, so any type of surgery was obviously a challenge. Mütter focused on what we now call plastic surgery to help the unfortunate who, either through bad luck with genes or misfortune in life, had horrible deformities. Aptowicz notes, “In regular surgical lectures, patients rarely understood the trouble they were in. When the knife first pierced the skin, they could come to the sudden realization that a life without this surgery might still be a happy one. . . . Patients of les opérations plastique, however, were often too aware of their lot in life: That of a monster. . . . It was not uncommon for these patients to enter the surgical room fully prepared to die. Death was a chance they happily took for the chance to bring some level of peace and normality to their mangled faces or agonized bodies.”

After studying in Paris, Mütter returned to Philadelphia to teach at Jefferson Medical College. He made waves there by acting in a way that seemed eccentric, at least for a professor of medicine. Not only did he dress in snazzy silk suits (and that sporty umlaut), Mütter greeted his students gleefully as they entered the lecture hall. Typically, a professor, many of whom had God complexes, would wait for the class to be seated before deigning to enter. Mütter even went so far as to ask questions during his lecture, promoting dialogue in the class as opposed to a dry recitation of a speech. This was unheard of in U.S. academia.

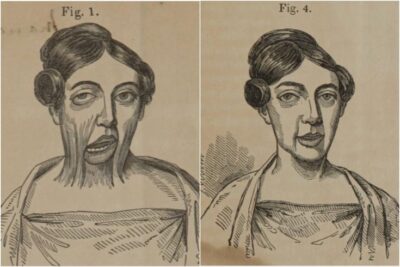

Mütter spent most of his surgical career working to “unmake deformities,” and he even had a procedure named for him. The Mütter flap was used to help burn victims, often women who were unfortunate enough to have their highly flammable clothing catch fire while cooking. In this procedure, Mütter grafted skin from the patient’s back by curving it around the shoulder, creating a “flap.” While this was extremely painful for the patients (again, no anesthesia), they were grateful to be able to return to some semblance of normalcy.

Illustration from Mütter’s publication about the flap surgery

During his 30ish-year career, Mütter collected his “oddities” as a means of teaching surgery to his students. In the last years of his life, he worked to find a home for the collection so that it could continue to serve as an educational tool for aspiring doctors. In 1858, just a few months before Mütter died, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia agreed to establish the Mütter Museum to house the collection.

I recommend this book not only for what it does to shed light on Thomas Mütter and his amazing contributions to medical science, but also because Aptowicz’s attention to what else was happening in the United States at the time. She addresses the way women were barred from practicing medicine because “they cannot stand the strain.” This didn’t stop a group of Quakers from founding the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1850. She traces the origin of the first time abortion was officially deemed illegal in the United States to the death of Eliza Sowers in 1839. Because Mütter was active in the years leading up to the American Civil War, abolitionism and the attitude towards it in Philadelphia are also addressed. (Let’s just say the scapegoating expression, “They took our jobs” isn’t a recent invention.)

Aptowicz does all this in a very engaging, story-telling manner. I may have come for the “monsters,” but I left with a greater appreciation for Dr. Thomas Mütter and the people of the age in which he lived.