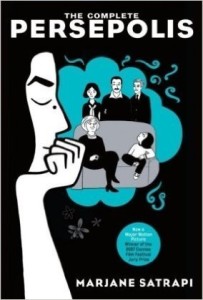

Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel is both an autobiography and an historical/political education. Her simple yet bold black and white drawings beautifully illustrate the story of her childhood in Teheran in the early 1980s, her teen years in Vienna and her return to Iran in 1989. As an observer of and participant in Iran’s revolutionary upheaval, Satrapi gives a personal view of events and their effect on her family’s welfare while neatly outlining the complicated and complex national story that serves as their context. This is a story of statewide repression and of personal independence.

Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel is both an autobiography and an historical/political education. Her simple yet bold black and white drawings beautifully illustrate the story of her childhood in Teheran in the early 1980s, her teen years in Vienna and her return to Iran in 1989. As an observer of and participant in Iran’s revolutionary upheaval, Satrapi gives a personal view of events and their effect on her family’s welfare while neatly outlining the complicated and complex national story that serves as their context. This is a story of statewide repression and of personal independence.

The story begins in 1980 when Marjane is 10 years old. The Islamic Revolution has overthrown the Shah, who is in exile, but it has also unleashed religious fundamentalist forces that crack down on personal liberties, especially where women are concerned. Marjane’s family is educated and politically active. Her grandfather and uncle were political prisoners, and her parents and their friends are members of the socialist intelligentsia. The Satrapi family history is a history of modern Iran; they suffered under the Shah and again under the revolution. The child Marjane feels the effects of the revolution at school, where she is required to where a veil and the curriculum changes to reflect the new religious fundamentalism; and she feels it socially, as friends leave the country or are killed in the ensuing war with Iraq. The section of the novel that deals with the bombardment of Teheran and the effects of war and revolution on its people would probably be a revelation for most Americans. The cultural differences and tumultuous history between Iran and Iraq are poorly understood by most Americans, including our leaders.

At the same time that her country is experiencing this upheaval, Marjane is growing up and learning her own mind. She tries to reconcile her personal religious belief with her fervent Marxism, she begs to attend rallies with her parents, and imagines herself as “… justice, love and the wrath of God all in one.” She is fiercely devoted to her grandmother and uncle, and takes pride in her family’s activism, but she is also aware of the cost of this activism — torture and death. At school, Marjane wears jeans and jewelry under her chador, incurring the wrath of the principal. Marjane is not afraid to argue with authority and even get physical when required. Eventually, her parents decide that Marjane’s future would be better if she left Iran to be educated in Vienna. The years that she spends in Europe, without her parents, are a time of experimentation and intellectual growth but also depression and abuse. Marjane struggles to learn a new language and try to fit in to a culture that is hostile to foreigners. Her string of roommates and her boyfriend all introduce her to things lost to her in Iran — open political discussion, drug use, freedom to dress and present oneself as one pleases — but there is a price to be paid for this. It’s easy to make a young foreign woman a target for abuse, and when Marjane fights back, she finds herself alone. Increasingly, she feels the pull of family and Iran, and returns home in 1989 at the age of 19. Yet even when she returns to her roots, Marjane struggles with fitting in. She has missed much of the war and struggle that her family and friends endured and now she is without the freedoms — intellectual, cultural, and otherwise — that she enjoyed in the West.

My calamity could be summarized in one sentence: I was nothing. I was a Westerner in Iran, an Iranian in the West. I had no identity. I didn’t even know any more why I was living.

When Marjane makes an effort to get involved — becoming an aerobics instructor (!), enrolling in the university, falling in love with another student named Reza — she experiences some fulfillment and makes some close friends who think as she does. Yet Marjane finds herself unsatisfied and frustrated — with Iran, with her boyfriend/husband, and with other women. She engages in subversive activities like attending parties, but she cannot pursue her career ambitions or be fully herself, so she leaves again for the West, this time for Paris, which is where she currently resides.

Marjane Satrapi’s story is surprising and inspiring. It should be required reading for US high school students and particularly for young women. I’m old enough to remember when there was a Shah of Iran, when he and his family went into exile and when the Ayatollah Khomeini was the leader of Iran. I vividly remember the hostage crisis (I was in middle school and it was on the news every night; we wrote letters and sent cards to the hostages), President Carter’s failed attempt to rescue the hostages and their eventual release. But of course, we never really learned the history of Iran or the political and religious roots of the revolution. We knew nothing of the average Iranian, just as we knew nothing of the average Russian under Soviet rule, which made it so much easier to demonize or simply denigrate entire populations. Satrapi’s descriptions of life, history and her own desires as a modern educated intelligent woman should make us all feel perhaps a little ashamed that we haven’t bothered to know her, her fellow Iranians, Iraqis, Kuwaitis and everyone else “over there” whom we lump together. I like that she is so assertive, that she hasn’t backed down before “power.” I think she is a wonderful example for young women; don’t take your advantages for granted because you could lose them, and don’t be afraid to speak up for yourself and what you care about.