After reading Schmookaria’s review, I ran right over to Amazon and picked this up. And I enjoyed every minute of it!

After reading Schmookaria’s review, I ran right over to Amazon and picked this up. And I enjoyed every minute of it!

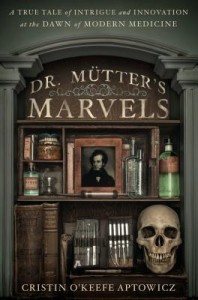

This is the story of Dr. Thomas Mütter and the birth of modern medicine in America. I’ll just steal this part from Amazon’s summary because I like how they put it so succinctly:

Brilliant, outspoken, and brazenly handsome, Mütter was flamboyant in every aspect of his life. He wore pink silk suits to perform surgery, added an umlaut to his last name just because he could, and amassed an immense collection of medical oddities that would later form the basis of Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum.

Although he died at just forty-eight, Mütter was an audacious medical innovator who pioneered the use of ether as anesthesia, the sterilization of surgical tools, and a compassion-based vision for helping the severely deformed, which clashed spectacularly with the sentiments of his time.

Aptowicz jumps around in time so this narrative is mostly, but not really, linear. We get a glimpse into the Paris surgeries and hospitals where Mutter was first introduced to surgery radicale. We get a taste of Philadelphia as it was coming into its own as the epicenter of American medical education–in a time where becoming a doctor wasn’t standardized and medicine was largely, amazingly, guesswork, especially by our modern standards. We get terrifying glimpses of 19th century medicine, including what was considered reproductive health, phossy jaw, and amputations before the era of anesthetic.

Mütter entered this world as a young doctor who had chosen his profession out of a sense of urgency–his whole family had died by the time he turned 7–and compassion. He was among the first to provide post-surgery care (rather than sending patients home in a bumpy carriage) and fully inform the patients about the risks and rewards of the surgeries they were about to undertake. His plastic surgeries were often performed on people who literally had no other option besides death: women whose dresses had caught on fire, for instance, who could no longer blink or turn their heads because of the deep scar tissue. They were monsters, gruesome, un-marriageable, undesirable, out of luck and hope. Radical surgery was their only hope to make life bearable, and Mütter took on this responsibility/opportunity with both compassion and innovation, throwing himself into his work and coming up with new, daring ideas for treatment. This guy crammed all he could into his time on this mortal coil, and reading about it is inspiring.

Throughout the book, we also learn about the lifelong professional rivalry between Mütter and Dr. Charles Meigs. Aptowicz paints Meigs as a foil to Mutter’s forward-thinking, innovative personality and a stark example of how drastically the world of medicine changed in one lifetime. Meigs was what you might call old school, a man who would perform gynecological exams on up to 14 women a day without washing his hands between appointments. (I KNOW.) But while that can perhaps be chalked up to being a man of his times (many doctors in fact took pride in how bloody their aprons got; germ theory wasn’t really a thing; no one really understood how infections or contagions worked) he also stood his ground til the last against new science and innovations (yes, including theories of infection and cleanliness)–to his ultimate shame. Aptowicz paints both men with verve and uses them and their vastly different personalities to show how strange the world of medicine was in the 1840s.

Aptowicz’s writing is very easy to read. It’s not quite a novel, but it does sometimes read like one, despite its often grim subject. She clearly did her homework, and the citations at the end of the book are lengthy.

So, who wants to go to the Mütter Museum with me?